On Satisfaction

INTRODUCTION

“To live a more meaningful life, we don’t need another vacation, a new hobby, or another workout routine. We don’t need an endless stream of self-improvement projects piled onto an already overstressed life. What we truly need is a life we’re not trying to escape, a life where play and joy are woven into our everyday work, allowing us to experience deeper fulfillment and uncover the breakthroughs we’ve been searching for.” - Chase Jarvis

There are 8 billion people on the planet today. Each of us is unique and complex, with our own desires and goals. But underneath all this complexity, we ultimately want the same thing out of life - to feel satisfied.

That may sound deceptively simple - and maybe it is. How we define satisfaction and how we pursue it varies widely depending on our upbringing and environment. Yet across all those differences, one truth remains: we want to feel good about our lives and how we’ve spent our time.

Still, many of us find ourselves stuck on some version of the hedonic treadmill - chasing the next accomplishment, believing satisfaction lies just beyond it. But it remains a moving target we rarely seem to reach.

If what we want is so simple, why do so few of us seem to find it for ourselves?

In my experience, several factors prevent people from finding satisfaction:

We overrate the abstract concept of “success”

We fail to define it properly

We compare ourselves to people who define “success” differently than we do

We underrate the “average” life

We overlook the positives of “average”, lower-status roles

We undervalue the benefits of routine

We’ll explore each of these ideas in more detail, but the bottom line is this:

The quickest way to satisfaction isn’t via achievement or status. It’s by finding contentment and gratitude in where we are today. To shoot you as straight as possible - satisfaction is found by embracing the “average” life.

To put it in more practical terms - we don’t find satisfaction by becoming a millionaire professional athlete, pop star, or titan of industry. There are countless examples of people who reach extraordinary heights of success, yet still wrestle with a sense of dissatisfaction. This is great news too, because let’s be real: most of us aren’t going to become any of those things. But even in our own fields, the reality is that most of us will fall much closer to the “average” section of the bell curve.

Maybe that comes off as a bit defeatist or depressing, but I hope I can convince you to find this somewhat liberating. If satisfaction is found independently of any external achievement, it means we already have everything we need to find satisfaction in our own lives - right now. All that’s left to do is start winning the battle between our own ears and finding security in who we are today.

I think many of us chase certain growth goals or accomplishments in an attempt to keep up with the Joneses. Finding gratitude in where we are today allows us to chase growth goals from a place of genuine desire and excitement, as opposed to playing an anxiety-riddled game of catch-up.

In other words: if we can be happy today - at “average” - anything else that comes our way is gravy.

“SUCCESS” IS OVERRATED

As mentioned above, we tend to overrate the abstract idea of “success” for two primary reasons. First, we often fail to define success clearly - if we define it at all. Second, we compare ourselves to others who pursue different versions of success, often at costs we wouldn’t choose for ourselves. Let’s explore both dynamics more deeply.

1) We fail to define “success” properly

One fundamental mistake many of us make is confounding success with status. Though related, they’re not the same. Success is internal - we define it and determine when we meet it. Status is external - it’s comparative, depending on how others perceive us. Waking up to this distinction unlocks two critical insights.

First, defining success is a choice - one that most people leave unmade. When we fail to consciously define success for ourselves, we generally absorb society’s default version: a prestigious job title, a certain income level, a trophy, or a line on our resume. These goals aren’t inherently wrong, but chasing them without true personal alignment often leads to exhaustion, burnout, and a persistent sense of dissatisfaction. You can pursue traditional goals if they genuinely resonate with you - but the key is to choose them, not inherit them.

(If you’re interested in a deeper exploration of this idea, I recommend thinking about your goals in the context of "resume virtues vs. eulogy virtues" - this is a framework that’s helped me personally think more clearly about where I derive satisfaction, and the kind of life worth aiming for. In short, resume virtues are skills you bring to the market, while eulogy virtues are the ones people remember you for when you’re gone.)

Second, and maybe most liberating: you can be successful without having high status. The more your definition of success diverges from traditional measures of status, the more uncomfortable this might be. It may mean taking a less glamorous job, earning less money, or stepping outside the script your peers expect you to follow. But clarity brings courage. When you truly own your personal definition of success, you’re free to pursue a satisfying life without seeking or depending on external validation.

The call to action here is simple enough: define success for yourself, and think about how closely it relates to status. Even if you don’t fully achieve your vision, the mere act of honest self-examination often shifts your mindset closer towards a sense of satisfaction.

2) We compare ourselves to people who define “success” differently than we do

Defining success on your own terms is crucial - it transforms your relationship with satisfaction in two important ways.

First, it helps you choose your cohort. In other words, once you define success for yourself, you can more deliberately identify the types of people worth admiring or emulating. Comparison is a natural human tendency we’ll always contend with, but if we must compare, we should at least be intentional about who we’re looking to for inspiration.

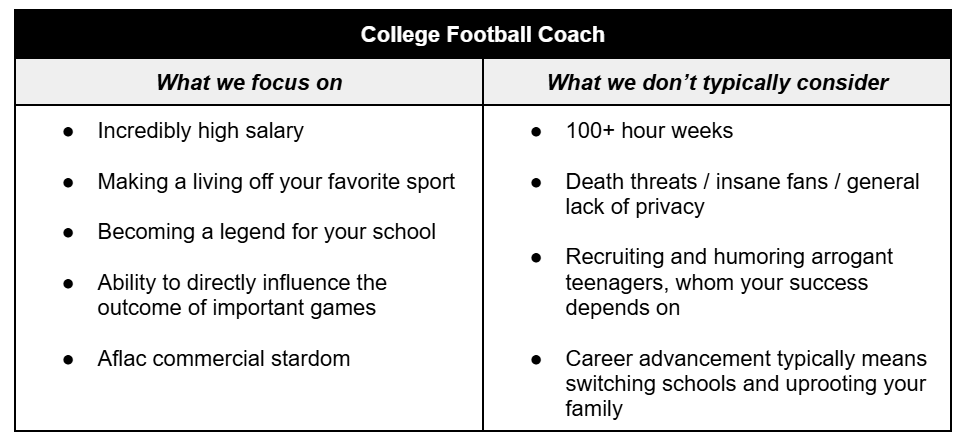

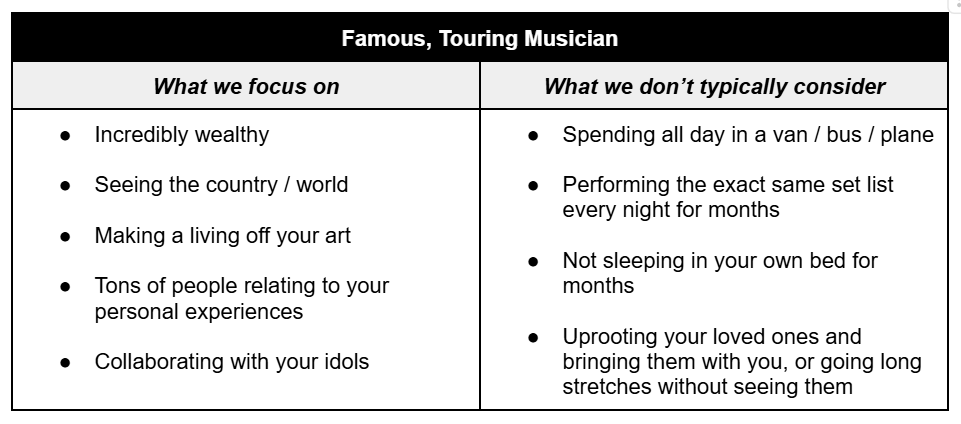

When we aren’t deliberate, we often default to admiring people in high-status roles - without fully considering the sacrifices those roles require. Worse, we tend to focus only on the glamorous aspects of their lives while overlooking the trade-offs. Two examples illustrate this pattern:

These examples lead to a second, deeper implication:

Your definition of success must also define the sacrifices you're willing to make.

If you’re absent-mindedly admiring someone with extreme status, but aren't prepared to endure the hardships that come with it, you’re setting yourself up for dissatisfaction. Extreme success often demands extreme trade-offs. Said differently: if you’re unwilling to endure the “cost” column of someone’s life, it doesn’t make sense to envy their “reward” column.

I can already hear someone thinking, “But Keith, if I were compensated like them, of course I’d be willing to absorb those trade-offs.”

But here’s the rub: you have to endure the sacrifices before you enjoy the rewards. In almost every high-status role, the heavy cost is paid upfront - long before the glamor and recognition arrive.

You always have a choice:

You can aim for a definition of success closer to traditional prestige - but know it will likely require extreme sacrifices.

Or you can pursue a more personal, non-traditional definition of success, accepting a different (and often gentler) set of trade-offs, like sacrificing external validation.

Both paths involve sacrifice - the difference lies in which costs you’re willing and able to absorb.

By choosing the right cohort and realistically assessing the trade-offs you’re willing to make, you dramatically increase your odds of finding satisfaction in your day-to-day life. Before you let comparison steal your contentment, ask yourself two simple questions:

Would I actually want my daily life to look like this person’s?

Am I realistically willing to make the sacrifices required to get there?

If the answer to either question is "no," it’s time to stop measuring yourself against that person. They’re playing a different game, aiming for different goals, constrained by different sacrifices.

(Holding luck constant, of course.)

“AVERAGE” IS UNDERRATED

We’ve spent time unpacking why high-status roles are often overrated - and how our obsession with them can undermine personal satisfaction. But there’s another side to this equation: we also tend to underrate the value of a more “average” life.

Before we go further, let me be clear: embracing an “average” life isn’t about settling or giving up. It doesn’t mean trading ambition for apathy. In fact, I’ve written before about the paradox of holding both gratitude and ambition at the same time - and that idea is at the heart of what follows. What I’m advocating here is a mindset shift: one where satisfaction isn’t postponed until we achieve something “impressive”, but can be cultivated in the lives we’re already living. When we start from a place of contentment, our growth goals become less about chasing validation and more about genuine curiosity and personal meaning.

Even if we’ve clearly defined success on our own terms and chosen the right people to emulate, we’re still vulnerable to two common traps:

We overlook the positives of traditionally lower-status, “average” roles

We undervalue the benefits of routine and stability

Let’s look at each more closely - starting with the quiet upsides of roles we’ve been conditioned to dismiss.

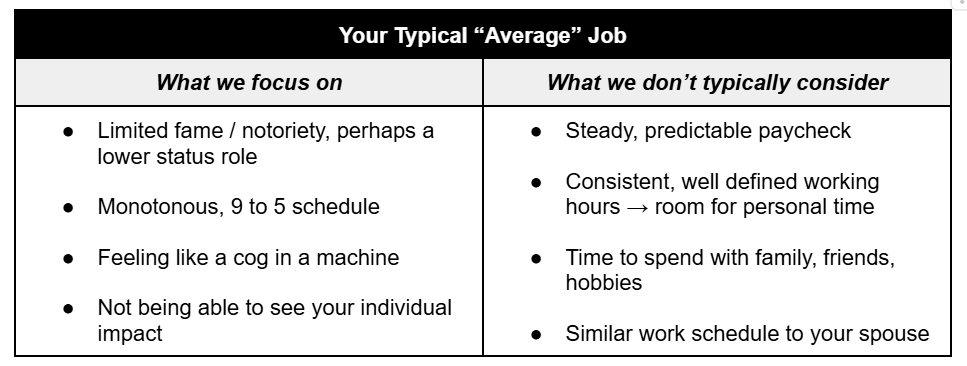

1) We overlook the positives of “average”, lower-status roles

When we look at high-status lives from the outside, we often see the highlight reel - fame, influence, admiration - while ignoring the costs that come with them. With our own lives, we tend to do the opposite: we zero in on what’s missing or monotonous, downplaying the meaningful, positive aspects we already have. We romanticize what we don’t have and become blind to the quiet value of what we do.

At its core, I think this dynamic stems from one overarching cultural norm: we’ve been taught to always strive for more. As a result, we feel a sense of shame in being content with “average,” lower-status jobs - even when those jobs might quietly deliver the kind of stability, freedom, and balance that lead to genuine satisfaction. Case in point - when was the last time someone proudly declared their dream was to be a middle manager?

Middle managers, in particular, have become cultural punchlines - reduced to cogs in the corporate machine, endlessly circling back via email and sitting through status meetings. Sure, these roles can include their share of bureaucracy and boredom. But they also come with upsides we rarely acknowledge.

These benefits aren’t trivial - they’re foundational. A steady income, regular hours, and mental energy left at the end of the day can enable a deeply fulfilling life, one rich in relationships, creativity, and community. Yet we rarely give ourselves permission to celebrate this. We minimize it because it doesn’t conform to the polished narrative of success we’re constantly sold.

The beauty of choosing satisfaction over status is that you gain agency. You can design a life that aligns with your values - including how much risk, ambition, or visibility you’re willing to pursue. For some, high-status roles genuinely fuel a deep sense of purpose and pride. But for many others, satisfaction may come not from recognition, but from balance: steady income, protected time, and enough energy left over to pour into the people and passions that matter most. In those cases, keeping the day job isn’t settling - it’s a deliberate choice to prioritize what matters most. That’s not failure. That’s strategy. And in a culture that constantly urges us to chase more, recognizing that you already have enough is often the first real step toward satisfaction.

Said differently: when you stop chasing what the world tells you to want, you finally make space to enjoy what you already have.

2) We undervalue the benefits of routine

Like middle-manager roles, routines often get a bad rap. Both can be legitimately valuable, yet both are routinely misunderstood, dismissed, or frowned upon by modern culture.

With routines in particular, we tend to associate them with boredom or stagnation - something we fall into rather than choose. Social media only amplifies this mindset, feeding us a highlight reel of constant novelty that makes everyday life seem dull by comparison.

But routine isn’t just necessary - it’s incredibly beneficial. Without it, life would be chaos. Imagine having no default structure: every day would require dozens of tiny decisions just to get started. What should I wear? What should I eat? Where should I go? What should I do today? This kind of unpredictability may sound exciting in theory, but in practice, it leads to decision fatigue and a scattered mind. A good routine eases that burden, conserving mental energy for the things that matter most.

The key is to stop seeing routine as the enemy of joy and start seeing it as the scaffolding that supports it. The right routine doesn’t have to be rigid - it should be built intentionally to reflect your values. Make space for what you love. And just as important, leave room for what you don’t yet know you’ll need - unstructured time, spontaneous detours, space to wander. Design your routine to include structure where it matters most, and intentionally block time for unplanned creativity and spontaneous adventures. It’s crucial to remember that the reason these “special” moments feel so special is because they’re set against the backdrop of our ordinary days.

Your whole life can’t be novel. And it shouldn’t be. That would be exhausting. Satisfaction doesn’t come from constant stimulation - it comes from rhythms and routines that create the space to find meaning, stability, and presence.

CONCLUSION

So many of us believe that if we could just hit the next milestone - or take that long-awaited vacation - we’d finally feel satisfied. We imagine that peace lives just beyond the next achievement, the next break, the next external fix.

But the real battle is the one between our own ears. Most anxious people who go to Cancun don’t come back calmer - they just end up being anxious on a beach in Cancun. I’ve come across a quote several times recently that applies perfectly here:

“Wherever you go, there you are.”

And “where you are” isn’t just geography. It’s your job. It’s your home. It’s your habits. It’s your routine. The hedonic treadmill keeps spinning, and we keep running - hoping the next thing or the next place will finally deliver satisfaction. But satisfaction was never out there to begin with. It has to be built from within. That starts by stepping off the treadmill - or at the very least, recognizing that you’re on it.

By decoupling success from status, being honest about the trade-offs behind other people’s lives, and embracing the quiet power of routine, we can start to build a version of satisfaction that doesn’t rely on escape or applause. It’s not about lowering the bar. It’s about learning to see the life you’re already living with clearer eyes and deeper appreciation.

Maybe this whole essay just sounds like a guy that’s sniffing 30 years old coming to terms with the fact that he’s probably not making the Forbes “30 under 30” list. And maybe that’s exactly what it is.

Maybe it’s also why this message is worth hearing - not from another millionaire thought leader on LinkedIn, but from a pretty average guy still figuring it out in real time.

And if that’s the case - if this is just me trying to take my own medicine and learn to find peace without external validation - then maybe that makes this whole perspective even more compelling, not less.

It’s on each of us to examine our lives, define what we truly value, and build satisfaction from the inside out.

Thank you to James Blanchard and Warren McKee for reading various versions of this essay.