One Year In // The Charter

I am going to try to sell one thing on this website in 2026

“I don’t know where this is leading me, but I like the direction I’m headed…” - Mel Robbins (via podcast)

One Year Down

Howdy everyone! Early January 2026 marked one year since I stood up keith.diy. I figured that was as good of an opportunity as any to take a break from the self-helpy essays I’ve been locked in on recently, and take stock on how this whole experiment has gone.

Consider this a brief detour from our standard programming to:

Share a few learnings and realizations I’ve had over the past year of keith.diy

Give a clearer sense of how I’m thinking about the site moving forward

Outline some initial changes you may start to see as a result

Before we jump in, I want to take a second to express my genuine gratitude and appreciation for any and every single person who’s read one of my essays or visited the site over the past year. I know we’ve all got 25 different things vying for our attention at any given time, so I truly appreciate anyone willing to carve out the time to engage with this stuff.

The fact that anyone clicked on one of my links this year means more than I expected. While this site is ultimately “for me,” the feedback and engagement I’ve gotten has put real wind in my sails and helped me stick with it. It would be ideal if every single thing I said resonated with every single one of you, but I know that’s never going to happen - as always, take what’s useful and feel free to leave the rest.

One last note - many of the quotes and concepts I allude to in today’s essay can be found in Kevin Kelly’s “101 Additional Advices” - if you don’t read everything below, I recommend at least giving this one a quick scroll. Tons of helpful nuggets in there.

OK - context out of the way, let’s discuss the past year.

Building in Public

Looking back, a lot of what I wrote this past year probably felt a little repetitive. Same themes, same questions, same general tone. Despite all the writing about intentionality, that itself wasn’t entirely intentional. I was basically just writing for myself, trying to work through a couple of things that felt unresolved, and this site became the place where I did that out loud.

At a surface level, the original motivation behind keith.diy was simple: I wanted to become a more “creative” person. That’s still true, but I now think that framing was incomplete. This site has ended up being less about creativity in the abstract and more about reshaping how I think about myself - as well as how I actually spend my time.

For most of my life, my identity has been fairly narrow. I spent years thinking of myself primarily as an athlete. Once I realized I wasn’t going to make the league (meaning the MLS 🙁), that identity shifted. Slowly, and largely unintentionally, I began defining myself more and more by my professional life: the industry, the company, the title. Somewhere along the way, a disproportionate amount of my sense of progress and self-worth became tied to those markers.

Over the past year, keith.diy has functioned as a way to loosen that grip.

More than anything, this site is becoming a tool for building a kind of self-actualization muscle - getting more comfortable taking initiative, committing to ideas, and generating momentum without anyone assigning me a task or holding a deadline over my head. Writing publicly was simply the most accessible place to start.

Doing that in public is a crucial piece of the equation. I don’t need massive exposure or validation - just enough visibility to create a bit of pressure. Enough that I can’t quietly abandon things, but not so much that fear or ego get in the way of starting.

Releasing essays, standing up the site, and even trying a few stand-up open mics all followed the same pattern: low-stakes creative efforts that forced me to commit to a specific output instead of lingering forever in the thinking-and-planning phase. (Read: procrastination.)

The through-line here isn’t actually writing or comedy. It’s action - incremental progress. Taking ideas that live in my head and making them real, even when the payoff is unclear. Sometimes those things land, sometimes they don’t*. The point is to keep moving.

I don’t know exactly where this is going. I do know that it feels like the right direction - and for now, that’s been enough to keep me going.

The next two sections dive deeper into the two ideas that sat at the top of my mind for most of the past year, and ultimately led to many of my essays circling similar ground:

How I think about status and professional trade-offs

Whether I’ve been too risk-averse throughout my 20s

If you’re tired of hearing me wax poetic on those topics, or you’re more interested in where this site is headed, feel free to skim ahead to the “Next Experiment” section further below.

On Feeling Behind

Leaning into a more creative, self-directed path has been energizing. It’s helped me flesh out my own thinking. But it’s also forced me to confront some very real trade-offs, and the insecurity that comes along with them.

For most of my adult life, I’ve tried to optimize for a specific balance: doing work that’s at least somewhat interesting or beneficial, while still protecting time and energy for life outside of it. Even early on, when I was looking for my first job and had no real sense of what the corporate world would look like in practice, I can remember turning down interviews because I knew that if I got the offer, I wouldn’t be able to say no. I also knew those roles would require sacrificing just about every waking hour of my life just to keep up.

Over time, I’ve gotten close enough to see how a lot of the more traditionally “prestigious” paths tend to work. While I understand the appeal, I’ve never been compelled enough to make the sacrifices required to pursue them. The fancy name on a résumé or the status associated with a particular role has never felt worth trading away the other parts of my life. I want time with my wife, friends, and family. I like to exercise and play soccer. I can’t consistently operate on less than, like, seven hours of sleep. If you want traditional success, you’re usually going to have to sacrifice at least one of those. You’ll also probably have to get through case interviews, which, if we’re being honest, have never been my strong suit anyway.

As someone who’s fairly type A and has always taken pride in being a “high performer,” this approach created a minor identity crisis. It often felt like I was making an objectively stupid decision. Only in more recent years did I start encountering the now-popular idea of prioritizing direction over speed - a way of articulating something I’d felt intuitively, but struggled to justify when comparing myself to peers.

One line from Kevin Kelly has stuck with me as a useful reminder:

“The most common mistake we make is to do a great job on an unimportant task.”

In theory, ideas like this sound wise and grounded. In practice, they can feel pretty brutal. Choosing direction over speed often means watching others get very good at “playing the game” while you’re still trying to decide which game you even want to play. It means seeing people rack up impressive titles, promotions, and credentials while you’re still working through which path actually makes sense for you.

Through all the writing I’ve done over the past year, I’ve come to see this more clearly as the trade I’ve been making, whether I named it that way at the time or not. In practice, I’ve chosen sustainability over acceleration - prioritizing time, energy, and a fulfilling personal life over optimizing for the fastest possible climb up a corporate ladder.

And if we’re being honest, there’s likely some favorable storytelling going on here. I’m essentially positioning myself as the tortoise rather than the hare. I know how that story ends, and I’m choosing to believe it might hold true here as well - even if that belief is a little convenient.

Despite putting my finger on all of this, it doesn’t mean the insecurity disappears. It absolutely doesn’t. But over time, leaning more fully into creative work has helped recalibrate how I think about progress. I’ve become less fixated on whether I’m “behind” by traditional standards and more interested in whether I’m building a worldview and a set of skills that actually feel like my own.

To be clear, this isn’t a rejection of ambition. A raise would still be great. Career progression still matters to me. I’m just trying to be more intentional about which kinds of progress I’m optimizing for, and why. And candidly, the feedback and conversations that have come out of this site have felt more meaningful to me than any professional achievements to date**.

Getting Good at Starting

I spent a good chunk of my twenties reading essays and articles about how your twenties are the time to take risks. It’s the decade you’re supposed to commit to the grind, stay late at work, say yes to the difficult thing, and bet on yourself while the downside is still relatively constrained. No kids yet. Fewer obligations. Maximum flexibility. The message was consistent: this is the window.

As I approach 30, the cultural script would suggest that my risk-taking window is about to slam shut. Even if I know, rationally, that’s not actually how life works. This has led me to the same question numerous times over the past year: did I take enough risk in my twenties?

I’ve always been a fairly risk-averse person - it’s just who I am. I like stability. I like predictability. I like having a rough sense of how things are going to turn out. And while that disposition has helped me build a life I genuinely enjoy, it’s also forced me to confront the possibility that I’ve sometimes erred too far on the side of caution.

At the same time, I recognize that lingering on this backwards-looking question is just another version of dwelling on sunk costs. Which, after reading enough self-help, I know isn’t particularly useful. One line from Kevin Kelly has been a helpful reset for me here:

“Asking what-if about your past is a waste of time; asking what-if about your future is extremely productive.”

That quote helped reframe the problem. Instead of asking, “Did I take enough risk back then?” I’ve been trying to ask a more constructive question: How do I get more comfortable taking reasonable risks moving forward?

Said differently: how do I design situations that force me to grow, without blowing up a life I’m genuinely grateful for?

It’s no longer about answering whether I took enough risk in the past. It’s about creating small, contained situations where I force myself to take some now.

The Next Experiment: Selling One Thing

Writing these essays and trying my hand at stand-up has been awesome. I plan to keep messing around in both of those areas and continue building those habits, but they’re not the focus for this year. This year, my focus is on leaning into controlled risk-taking in a way that still fosters creativity, but starts to move a bit closer to entrepreneurship.

In the simplest terms possible: my goal for this year is to sell one singular product through this website.

I’m framing this goal narrowly on purpose. I’m not trying to start a company, build a brand, or turn this website into a side hustle. If I sell exactly one thing, I’ll consider it a success.

The real point is to force myself to work through the less glamorous parts of making something that resembles a business exist: building the infrastructure, deciding what to make, designing it, figuring out production, setting up payments, shipping it. All the unsexy, but necessary pieces of the puzzle.

It’s basically an exercise in building something from first principles - learning how the whole system works by being forced to deal with every part of it myself.

The first version of this needs to be as low friction, low upfront investment, and low downside as possible. Anything more complicated creates too many opportunities to overthink it, or talk myself out of starting altogether. In the immediate term, that almost certainly means I’ll be selling something print-on-demand. Think t-shirts, hoodies, stickers, things of that nature.

Practically speaking, you’ll likely start to see a few changes over the coming months:

The site structure will evolve. Instead of being so blog-centric, I’ll simplify the homepage and create clearer areas for writing, merch, and general overviews of what I’m working on.

Given the effort required to set up even a simple product operation, my writing cadence will likely slow down. Expect fewer essays this year.

Any products I release will likely touch on similar themes to the essays, possibly with short write-ups explaining the thinking behind them.

If you gave me your email to read essays, I’m not going to start blasting you with marketing emails. If I ever spin up a separate merch list, it’ll be built independently.

What Isn’t Changing

As I start to layer a more commercial angle into the site, I want to be clear about one thing: the core ethos isn’t changing. This has always been a quality-over-quantity experiment. Whether it’s an essay, a shirt, a piece of art, or something else entirely, the standard remains the same - everything here should feel intentional, thoughtful, and genuinely worth your time.

This approach is really a result of how exhausting the digital landscape has become. Between ads, sponsored posts, and constant attempts to sell something, it’s increasingly hard to just exist online without being marketed to. Social media isn’t really social anymore; it’s commercial media. This site isn’t going to become another piece of that noise. I’d much rather show up occasionally with something considered and interesting, even if that means showing up less often.

In that same spirit, I’m also interested in pulling this experiment in a more analog direction over time - things that foster real-world connection, like small pop-ups, in-person events, or projects that exist beyond a screen. I don’t have a fully formed vision for what that looks like yet, but it’s very much top of mind.

The Next Start

Longer term, my hope is that this self-actualization muscle eventually supports something more ambitious - likely somewhere in the realm of social entrepreneurship. I’m increasingly interested in the idea that business, at its best, can incentivize people to choose a product or service simply because it’s better, while any positive social impact emerges as a byproduct rather than being the pitch. I’m especially drawn to ideas around circular economies, but more broadly, I’m excited by the possibility of using markets and incentives as a force for good.

Selling a couple of t-shirts is obviously a long way from that. But learning how to design, produce, and ship anything feels like a prerequisite. It’s a concrete way to practice turning ideas into reality, rather than letting them live forever in my head.

Over time, I’ve come to realize that an ounce of application is worth a pound of knowledge. For a long stretch, I convinced myself that reading and thinking counted as progress. In reality, publishing my writing publicly was the first real experience I had of starting something. Selling one thing - anything - feels like the next step in that same direction.

As Kevin Kelly puts it:

“Many fail to finish, but many more fail to start. You can’t finish until you start, so get good at starting.”

This website was a start. Releasing my writing was a start. Trying stand-up was a start. Whatever this next experiment becomes is simply the next start.

In many ways, I think life is just about maximizing your shots on goal. Moving forward, I’m channeling my inner Monta Ellis - I may miss a thousand times, but I don’t plan to stop shooting.

Releasing this took a few weeks longer than I anticipated, so I should probably get to it.

*From my experience with comedy - things often do not land.

** Counterpoint: maybe I just need more impressive professional achievements?

The Story You Tell Yourself

Recognizing the power of storytelling - at cocktail parties and in your own head

“The story of your life isn’t about your life. It’s about your story.”

Introduction

Most of us spend an enormous amount of time trying to figure out what the “right” way to live is. We chase certainty (about careers, goals, values, etc.) believing that once we have the answers, peace will follow.

But life rarely improves through certainty - it’s often an unrealistic goal to begin with. It improves through intentionality - choosing how to think, what to prioritize, and how to respond even when the answers remain unclear.

We don’t get to choose most of what happens to us, but we do get to choose how we interpret it. And that choice, often made unconsciously, takes the form of a story.

The story we tell ourselves about our career determines whether it feels meaningful or draining. The stories we tell about our setbacks determine whether they feel like evidence of failure or part of the process. The story we tell about our lives becomes our worldview.

This essay explores a simple but powerful idea: that storytelling may be the most important skill we develop - not because it helps us entertain or persuade others, but because it’s the primary way we exercise control over how life feels while it’s happening.

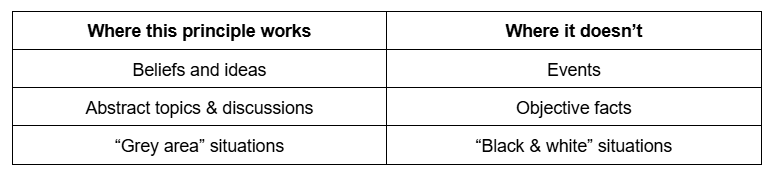

This isn’t about delusion, blind optimism, or toxic positivity. It’s about choosing between multiple plausible interpretations - and being intentional about which ones we let run our lives.

What Stories Do

If storytelling really is the medium through which we interpret our lives, it’s worth asking what stories actually do for us, and who we’re telling them to.

At a basic level, most of the stories we tell serve one of three purposes. They help us entertain, inform, or convince.

Entertain

This is the most obvious use of storytelling. A large portion of everyday conversation is spent recounting the past: funny missteps, small victories, embarrassing moments, and shared memories. These stories aren’t just about what happened, they’re also about how we choose to frame it. We emphasize certain details, downplay others, and search for humor or irony as we recount the past.

Inform

We don’t always think of information-sharing as storytelling, but narrative structure is often the clearest way to communicate what happened and why it matters. Stories help us organize cause and effect, explain interpersonal dynamics, and make complex situations easier to follow. They turn scattered facts into something coherent.

Convince

Whenever we’re trying to resolve a disagreement or bring someone around to our point of view, we rely on narrative. We walk someone through how we arrived at a conclusion, the evidence we used to get there, and why our position makes sense. Even when we think we’re “just stating the facts,” we’re usually walking someone through our own reasoning - a story designed to persuade.

These three functions show up across almost every context in our lives. But the more useful way to think about storytelling isn’t by what the story is doing - it’s by who it’s for.

Who We’re Telling Them To

Broadly speaking, we tell stories to three audiences: friends and family, coworkers, and ourselves.

Friends and Family

In social settings, storytelling is usually oriented toward connection. We entertain each other, share updates, and trade stories that reinforce shared identity and strengthen bonds. Historical accuracy or polished delivery often takes a back seat to shared context and inside jokes.

Coworkers

In professional contexts, stories become more pragmatic. We use them to project credibility, communicate value, and influence outcomes - particularly ones that we think will bestow us with a promotion or a nice raise. Job interviews are an obvious example: we take years of experience, selectively package it, and present it as a coherent narrative of growth and competence. Professional stories often aren’t just about the facts, they’re about what those facts signal about us.

Ourselves

Then there’s the audience that never leaves - the one that hears every version of every story. We are constantly narrating our own experience: connecting events, inferring cause and effect, and deciding what whatever just happened means. This internal story runs automatically and continuously, shaping how we feel about our work, our relationships, and our progress. Over time, it hardens into something bigger: a worldview.

When you put all of this together, a pattern emerges. The same storytelling tools we use socially to entertain, inform, and convince… don’t disappear when the conversation ends. They turn inward. And when the audience is ourselves, the stakes are much higher.

The Audience That Never Leaves

Once stories turn inward, they stop being occasional and become constant. The audience is always present, and the narration never really turns off. We are always absorbing, processing, and interpreting information - consciously and unconsciously. Over time, those interpretations become habits. And habits become defaults.

If your internal story tends to lean negative, life will feel heavier than it needs to. If it leans generous or curious, the same set of circumstances often feels more manageable. Nothing external has changed, only the interpretation.

This is why internal narratives carry so much weight. We don’t just tell them once - we tell them continuously. We repeat them to ourselves, thousands of times, over and over again. Philosophies like Stoicism emphasize a useful distinction here: between what’s within our control and what isn’t.

We can’t control most of what happens to us. But the meaning we assign to what happens - the story we tell ourselves about it - is largely within our control. When we can win the battle between our ears, almost anything life throws at us becomes more manageable. When we can’t, even objectively good circumstances can feel unsatisfying or hard to enjoy.

This doesn’t make life easy. But it does make it workable.

One of the clearest illustrations of this comes from Hope for Cynics by Jamil Zaki, where he revisits the parable of Sisyphus. If you don’t recall, Sisyphus was the guy condemned to push a boulder up a hill for eternity, only to watch it roll back down every time.

As Zaki puts it:

“The premise is set. The boulder must be pushed. Whether it’s a tragedy, a comedy, or a drama is up to the one doing the pushing.”

The circumstances don’t change, but the story does.

Most of us won’t be sentenced to push boulders forever, but we all have routines or responsibilities we’ve come to dread. The point isn’t to pretend they’re fun or meaningful when they aren’t. It’s to avoid letting our internal narration make them worse than they already are.

Your internal monologue will never stop - you might as well shape it deliberately.

From Stories to a Worldview

Over time, these repeated interpretations compound. They don’t just shape how a day feels - they shape how life feels. The stories we tell ourselves gradually harden into assumptions about what life is for, what matters, and what success looks like. Eventually, they crystallize into a worldview.

My working theory is that most of our internal monologue clusters around two high-level narrative tendencies.

Some people are wired to notice progress, gaps, and inefficiencies. Their attention gravitates toward stories about goals, optimization, and forward motion. Life, through this lens, becomes a problem to solve - a calling to find, an impact to maximize, a trajectory to stay ahead of. The underlying question is often some version of: Am I doing enough?

Others are more attuned to experience itself. They notice novelty, enjoyment, and presence. Their stories emphasize what feels interesting, satisfying, or worth savoring in the moment. Life, through this lens, is something to be appreciated rather than solved. The underlying question tends to be: Am I enjoying myself?

These aren’t opposing truths, and neither worldview is inherently right or wrong. They’re simply different ways of framing the same raw material: our lives.

The problem is that our default storytelling mode is largely automatic. We don’t consciously choose how we frame our internal monologue - our disposition largely does that for us. Left unchecked, we tend to over-index on one narrative and neglect the other.

This tension shows up everywhere: between achievement and enjoyment, seriousness and play, knowing the “point” of life and simply living it. But once we notice this tension, we gain a lever. We have a choice. The goal isn’t to pick the correct story - it’s simply to be intentional about the story we tell ourselves in the first place. To actively shape the lens through which we experience our lives.

This matters more than we like to admit. No matter how objectively good a life may be (if you’re reading this, odds are you’re already in the top 1–5% of global income), if we don’t experience it that way, it doesn’t feel good. We’ve all seen this: the deeply unhappy celebrities, founders, and millionaires who “won” on paper but seem to hate their own lives.

This is where storytelling becomes a practical skill. By becoming more intentional about which narratives we foreground, and which ones we temporarily quiet, we can counterbalance our natural tendencies. When anxiety creeps in, we can elevate gratitude and enjoyment-centered stories. When we feel stagnant or unmotivated, we can lean into progress and ambition-centered ones.

This isn’t about delusion or pretending to be someone we’re not. It’s about actively shaping stories that keep us centered, rather than riding an emotional roller coaster with no say in the matter.

The Story You Shape

So why does any of this matter?

It matters because the story you tell yourself sits upstream of almost everything else. How you frame your own experience quietly determines how you show up - in conversations, at work, in relationships, and in moments when no one else is watching.

There are practical benefits, of course. People who tell clearer stories tend to communicate more effectively. They’re often more persuasive, more engaging, and easier to trust. In a narrow sense, getting better at storytelling might help you sell an idea, land a job, or hold a room at a cocktail party.

But the deeper payoff is the feedback loop it creates. How you show up shapes how others respond, and those responses, in turn, reinforce how you experience the world. If you approach interactions with negativity or defensiveness, people tend to meet you there. When you bring curiosity, authenticity, or gratitude, the tone often shifts in kind.

When you learn to shape your internal narrative - to notice it, question it, and adjust it - you begin to experience your own life differently. You can actively shift it in a more constructive direction, and that change tends to ripple outward. Gratitude becomes easier to access. Interactions improve. Momentum becomes easier to find. Not because your circumstances have suddenly changed, but because you’re navigating them with more intention.

As we said up front: life doesn’t get better through certainty or status. It gets better through intentionality.

Storytelling is how that intentionality shows up in everyday life.

You’re going to tell yourself a story either way. Make it a good one.

We’re Not Dumb, We’re Missing Context

On Polarity, Assumptions, and the Degradation of Nuance

Introduction: The Case For Bottom-Up Nuance

Nuance and subtlety are on life support. Public discourse increasingly feels like a team sport where the goal isn’t understanding - it’s winning. We defend our “side” at all costs, prioritizing the appearance of being right over the more difficult work of getting to the best answer and ultimately driving the best outcome.

You’ve likely heard this complaint a thousand times, but I promise this isn’t another think piece blaming politics or social media. The real issue runs deeper. Many of us have stopped practicing the habits that make nuance possible. We complain that the world has become polarized and shallow, yet rarely examine our own role in that trend. The fix won’t come from institutions; it starts with how each of us forms and communicates our own opinions.

The more we rely on borrowed ideas and flatten others into caricatures, the less capable we become of genuine understanding. Rebuilding nuance begins with reclaiming our own thinking - and with remembering that intelligence, status, and value are all context-dependent.

This essay explores why nuance so often collapses in modern life, what the concept of context can teach us about intelligence and status, and how we can use a bottom-up approach to restore nuance through intentional opinion-making.

How Nuance Falls Apart

Society’s loss of nuance isn’t some mysterious cultural illness. It’s the compound effect of small cognitive habits many of us have fallen into - often without realizing it. There are countless factors driving polarization, but three in particular stand out: our growing passivity toward information, our lack of empathy for other people’s contexts, and our overconfidence in our own assumptions.

The Passivity Problem

We live in a world of infinite input. There’s more content available than any human could meaningfully process in a lifetime, and algorithms are happy to feed us an endless stream of opinions tailored to our tastes. The result is a subtle shift in how we spend our time: we consume more, but we think less. Put simply, though we’re absorbing more information than ever, we’re forming our own opinions less often.

That imbalance matters. Polarizing and reactionary content attracts the most attention, so it’s what we see most. When we casually adopt those takes and repeat them without filtering them through our own judgment, we reinforce the very dynamics that make discourse worse. It’s a self-reinforcing loop: outrage performs well, so it spreads; we see it, we share it, and the cycle repeats.

This isn’t about moral purity - everyone consumes. The problem is passivity: treating opinions as something to download rather than develop. Rebuilding nuance begins with reclaiming the creative side of thinking - taking the time to interpret what we consume before deciding what we believe. Run everything you hear through your own experiences and values. Don’t just accept information at face value.

The Empathy Gap

We judge ourselves by our intentions and others by their outcomes. When we make a mistake, we know the full context - we were tired, distracted, or under pressure, so we forgive ourselves. But when someone else stumbles, we rarely grant them that same grace. Their actions become their whole story.

This dynamic extends to a broader scale. We see ourselves as complex, multi-layered people, yet we flatten everyone else into one-dimensional characters in our personal narratives: the bad driver, the rude coworker, the inconsiderate stranger. When we cut someone off in traffic, we’re running late for an important meeting; when they cut us off, they’re an idiot who doesn’t know how to drive.

That’s the empathy gap - the distance between how we explain our own behavior and how we interpret everyone else’s. The truth, of course, is that no one is purely good or bad. Each of us is a collage of influences, experiences, and contradictions. Even the people who frustrate us most are, in some causal sense, products of their circumstances. If you were swapped with them cell for cell, you’d be them - grumpiness, flaws, and all.

Closing that gap is the first step toward nuance. When we remember that everyone carries their own mix of strengths and blind spots, it becomes easier to look for shared ground rather than proof of difference. We’re generally more alike than we think: most people just want safety, purpose, and love for themselves and the people they care about.

The more we practice that kind of empathy, the harder it becomes to flatten people into opponents. And once we stop flattening, we start noticing the next trap: how quickly we let a single detail - a belief, a label, or a vote stand in for an entire, messy human being.

The Assumption Trap

“Stereotype” is kind of a dirty word, but they do exist for a reason. Our brains are wired to fill in gaps and make quick judgments so we can navigate the world efficiently. But somewhere along the way, we started mistaking those shortcuts for truth. We’ve become comfortable extrapolating entire worldviews from a single data point.

Picture the kind of person who has an “In this house, we believe no human is illegal…” sign in their yard - now picture the kind of person furious that Bad Bunny is performing at the Super Bowl. You probably imagined two very different people, and you could probably guess where each one stands on a dozen unrelated social or political issues. And chances are, you’d be mostly right.

I’m not suggesting we approach every interaction as a blank slate - that would be exhausting and unrealistic. Stereotypes, at their best, are rough pattern recognition. They can even be useful starting points*. The problem isn’t that we make assumptions - it’s how confident we’ve become in them. We treat our guesses as fact and avoid conversations that might challenge them. We’d rather preserve the neat stories in our heads than test them against reality.

That’s the real trap: our assumptions don’t just make us wrong, they make us incurious. When we think we already know who someone is, we stop engaging with them altogether. We miss the chance to uncover the contradictions and nuances that make people (and conversations) interesting. By opting out of those interactions, we lose opportunities to refine our own thinking.

The reality is that most of us hold inconsistent or even contradictory beliefs somewhere. That’s not a flaw - it’s often the sign of a mind doing its own filtering, wrestling ideas through lived experience rather than blindly adopting them. It’s not realistic to expect anyone to hold perfectly consistent, rational beliefs. We’re all emotional creatures. In my experience, it’s often quite the opposite: the more contradictions someone holds, the more interesting they are**.

When these habits of overconfidence and avoidance scale up, they become cultural. We start to see entire groups as simple, misguided, or unintelligent - while granting ourselves endless complexity and context. After all, how could anyone possibly disagree with someone as thoughtful and multi-faceted as us?

But what we often dismiss as stupidity is usually just difference - a gap in context we don’t understand.

Rethinking “Smart”: The Context of Intelligence

Intelligence, like almost everything else, is contextual. Yet we often talk about it as if it’s a single, universal score - some fixed trait that sits neatly on a spectrum from smart to stupid. That illusion makes it easy to label people as intelligent or not, while ignoring the conditions that shape what they know and how they think.

So many of the qualities we admire - intelligence, talent, status, success - are deeply dependent on environment and experience. A genius in one setting can be useless in another. Whenever we compare ourselves to others on those traits, we’re flattening all the variables that make them meaningful: context, opportunity, background, and values. The doctor who thrives in a hospital setting might owe that expertise to a lifetime of structured education and access, while the farmer who never went to college might know more about soil chemistry and weather patterns than the doctor ever will. Both are intelligent - just in different contexts.

In reality, there are at least two kinds of intelligence worth distinguishing. The first is general intelligence - critical thinking that applies across contexts. The second is domain-specific intelligence - expertise that depends on a particular environment or body of knowledge.

General intelligence is less about raw IQ and more about habits of thought:

Sniffing out obvious BS

Recognizing your own limits (i.e., acknowledging when you’re not an expert)

Forming your own opinions instead of repeating others’

Communicating those opinions clearly

Explaining the reasoning behind them in a way that makes sense

People might not agree with where you land on an issue, but if they can follow the logic that got you there, you’ve already created the foundation for real dialogue.

Domain-specific intelligence, on the other hand, is when you are the expert. It’s the craftsperson, the coder, the nurse, the mechanic who can diagnose a problem that others can’t even describe. Knowing the limits of your own expertise - and deferring to others when they’re in their domain - is a form of intelligence in itself. It’s the humility to recognize that no one is smart everywhere.

A few examples make this obvious. The rural mechanic who might feel out of place at a black-tie gala could be the savior when the gala guest’s car breaks down in the middle of nowhere. The Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders - some of the most technically skilled dancers in the world - go home and resume their day jobs as nurses, office managers, and teachers***. Genius, skill, and competence all depend on setting. Often, those settings overlap neatly with class and geography. What looks like “ignorance” from a distance is often just intelligence tuned to a different environment - rural instead of urban, practical instead of academic, hands-on instead of theoretical. We miss that truth when we assume intelligence only counts if it comes with the credentials or characteristics of our own world.

When we start to see intelligence through this lens, the hierarchy flattens. “Smart” stops being a status label and becomes a description of fit - between a person’s knowledge and their context. When we lose sight of that, it becomes easy to divide the world into the intelligent and the ignorant - a false split that fuels the collapse of nuance across our culture. Instead of recognizing that everyone has strengths in different areas and engaging them accordingly, we simply write them off as stupid.

If we can relearn to see intelligence and status as contextual, we can also relearn to form opinions that respect complexity - in others and in ourselves.

Rebuilding Nuance From the Bottom Up

So what now? How do we actually bring nuance back?

If polarization and simplification are the natural byproducts of passivity, empathy gaps, and lazy assumptions, then the antidote has to be active - something we each practice intentionally. The work of rebuilding nuance won’t come from political institutions or the social media companies developing our algorithms; it has to start with how we think, speak, and listen.

At the simplest level, this means addressing the passivity problem head-on. We need to be more deliberate about engaging with the information that makes its way into our heads - accepting some parts, rejecting others, and shaping it all into opinions that actually belong to us. In practical terms, that means:

Generating your own opinions instead of regurgitating others’

Communicating your stance clearly, even when it’s incomplete or evolving

Explaining how you got there - the reasoning, trade-offs, and values that shaped your view

The goal isn’t to make everyone think alike; it’s to make disagreement productive again. When people understand how you reached your conclusion, they’re more likely to respond in kind. Even if you still disagree, you’re disagreeing on shared ground - with mutual respect for the thought that went into it. This is where common ground is found, and Bad Bunny Super Bowl rejecters begin to actually have fruitful discussions with “In this house we believe…” yard-sign people.

It’s not enough to endlessly consume content and call it awareness. You have to insert yourself into the process. Think critically about what resonates, what doesn’t, and why. The more intentional your inputs - the higher-quality, more nuanced, fact-based ideas you expose yourself to - the sharper your outputs become.

The nice part is that this isn’t just an individual skill; it scales. A culture of people who form and articulate their own opinions is, by definition, a culture that values context and complexity. It rewards curiosity over certainty, understanding over signaling, and creation over consumption.

Developing your own opinions is a creative endeavor - the daily act of making meaning instead of merely absorbing it. And if enough of us do that work, nuance might stop feeling like an endangered species and start feeling like a habit again.

Conclusion: Practicing Context

Nuance isn’t an abstract virtue; it’s a habit of curiosity, practiced one conversation at a time.

We shouldn’t expect this to be fixed from the top down. Political institutions and media companies aren’t exactly incentivized to slow things down and make us more thoughtful. Outrage is profitable. Simplicity is efficient. Picking teams is easier to sell than sitting with complexity. If we’re waiting on a platform redesign or a new batch of politicians to make public discourse more nuanced, we’ll be waiting a long time.

The good news is that the habits that create nuance are still completely within our control. We choose whether to treat other people as caricatures or as full humans with contexts we don’t yet see. We choose whether to adopt opinions wholesale or shape them ourselves. We choose whether to write people off as stupid or ask what kind of intelligence their world might actually require.

Practicing context means zooming out just enough to remember that everyone, including us, is a product of specific experiences, incentives, and environments. It means acknowledging the possibility that someone you disagree with might still be thoughtful in a domain you don’t understand. It means recognizing that “smart” isn’t a trophy some people get to keep - it’s a moving target that depends on where you’re standing.

None of this guarantees agreement. It doesn’t mean every viewpoint is equally valid or that we should stop drawing lines where it matters. What it does mean is that we take responsibility for the part we can actually control: how we think, how we talk, and how we treat the people who land somewhere else on the spectrum.

We can’t legislate nuance into existence. We can’t algorithm our way into empathy. But we can model it from the bottom up by forming our own opinions, explaining how we arrived at them, and giving others the grace of context. If enough of us do that, even in small, unremarkable ways, public discourse might start to feel a little less tribal - and a little more like what it’s supposed to be: a collective attempt to figure things out together.

*At their worst, we know that stereotypes tend to be blatant racism, sexism, or insert other form of prejudice here.

**They could also be a complete idiot. Your mileage may vary.

***This example may or may not be a result of watching the DCC Netflix documentary - against my will, for the record.

The Pragmatic and the Romantic

Sliding the spectrum between fact and feeling, exploring life between surface and story

INTRODUCTION

Several years ago, I was listening to an episode of How I Built This with Guy Raz. Sal Khan, the founder of Khan Academy, said something about tutoring that stuck with me:

“My little cousin was struggling with school, so what did her parents do? Like any good parents, they threw money at the problem.”

On the surface, he was right. Tutoring is, in fact, spending money to solve a problem. But the phrasing felt oddly cynical coming from someone who dedicated his life to helping students learn. That jarring moment eventually led to the following insight: for any given event, we can choose to see it pragmatically - at face value, facts and nothing more. Or we can see it romantically - as part of a bigger story, rich with meaning and possibility.

It’s tempting to conflate this with optimism vs. pessimism, but I think it’s different. Optimism is about positive vs. negative outlooks. Pragmatism vs. romanticism is about depth: accepting the shallow, surface-level view versus acknowledging deeper levels of meaning or value.

Realistically, though, this isn’t a binary choice. It’s a spectrum: how romantic we are about certain things compared to how pragmatic we are about others. And importantly, we can’t - and shouldn’t - always be romantic about everything. That would be exhausting and unsustainable. The power lies in sliding along the spectrum, choosing when to lean into romance and when to accept pragmatism.

Typically, this relationship works in one direction: we’re drawn to, and usually become better at, the things we’re already romantic about, while we avoid or feel dragged toward the things we view pragmatically. My core thesis is that by testing this relationship in the opposite direction - choosing romance where we’d normally default to pragmatism - we can enrich our quality of life. In other words: by being romantic about things we normally wouldn’t think twice about, we can find more beauty and enjoyment in what can often be a mundane life.

Example: A Case Study in Seeing Differently

Many of our favorite writers and shows are doing exactly this: finding beauty and meaning in the otherwise mundane, and making it compelling enough to hold our attention. One show that brought this idea home for me was True South*. In Season 7, Episode 4, the crew visits Little Rock, Arkansas.

In the SEC Network’s own words, the show “revolves around two food stories told from one place, which True South sets in conversation to make larger points about Southern beliefs and identities.” In other words, True South takes food - something easy to see pragmatically as sustenance - and reframes it romantically, as a medium for heritage, memory, and community.

The Little Rock episode is a perfect case study. The city itself is often overlooked, its state is often dismissed, and this particular story unfolds on Baseline Road - a part of town often avoided altogether. Through a romantic lens, however, the episode reveals layers of beauty in what most people would write off as “the bad part of town.” We see cultural tradition, celebration, and resilience.

I won’t rehash the whole episode for you, but at the center we have Jordan Narvaez, a thirty-something running multiple small businesses in southwest Little Rock: El Súper Pollo (a chicken al carbón tent), two grocery stores, and a Western apparel shop. We follow him through the day in his F-150 (that we learn he inherited from his father), watching him keep these enterprises alive as we learn more about his background and why he continues to run these businesses.

The reason this episode struck me so deeply is because it forced me to confront my own blind spot. I’ve been to Little Rock before, and in my pragmatic state of mind, I’ve never thought twice about Baseline Road. Candidly, the only real weight it’s held for me is as the “bad part of town.” But viewed through a romantic lens, the familiar became something else entirely - proof that in almost any situation, more beauty exists than initially meets the eye.**

At the end of the episode, Jordan’s businesses aren’t just businesses - they’re gathering places for his community. Jordan’s truck isn’t just another F-150 driving around Little Rock. It’s a way for him to stay connected to and honor his father.

It may not be a Southern food documentary for you, or a specific part of town, but odds are there’s some overlooked corner of your own life. What might you be writing off too quickly - and what might change if you looked again, romantically instead of pragmatically?

Application: How does this apply to our own lives?

So maybe you’re wondering why any of this matters beyond one episode of a niche food show. The point is that the same principle applies just about anywhere: we can make life feel richer by choosing to view the mundane through a romantic lens.

Two examples make this clear: careers and sports.

Example 1: Careers

Our jobs give us endless chances to test each end of the pragmatic - romantic spectrum. Take the example of a local businessperson who has opened 10 Courtyard Inn hotels. The pragmatic take is: “I’ve built a handful of hotels along the interstate.” Owning 10 hotels is pretty impressive, but in the grand scheme of things, Courtyard Inns are generally forgettable and unremarkable.

But the romantic version? “I’ve opened 10 places where families on road trips, workers away from home, and weary travelers could sleep and get a warm meal. Since opening, we’ve hosted more than 10,000 people.”

The facts don’t change, but the meaning does. Even in a job that feels ordinary or inconsequential, a romantic lens can highlight the value you bring to others.

Example 2: Sports

Sports might be the clearest split between pragmatists and romantics. On one side: skeptics who see them as nothing more than grown adults running around in uniforms, a modern “bread and circus.” On the other side: fans who see sports as culture-shaping forces that unite cities, create civic pride, and even spur broader change and community investment.

Both of these examples are a little trite and on the nose, but that’s kind of the point. The reality of each is somewhere in the middle: operating hotels isn’t necessarily life-changing work, but it does bring value. Sports teams do unite communities, but they’re not an essential service. That middle ground is where the pragmatic-romantic spectrum comes in. It gives us the flexibility to stay grounded in reality without losing the sense of romance that makes things exciting and meaningful.

Conclusion

We don’t get to choose all the circumstances of our lives, but we do get to choose the lens we bring to them. Pragmatism keeps us grounded in reality. Romanticism derives meaning, emotion, and impact from that reality. And somewhere between the two - sliding along the spectrum with intention - is where an ordinary life can begin to feel extraordinary.

Even Sal Khan’s story about “throwing money at the problem” can be read in two ways. Pragmatically, it’s a transaction - parents paying a tutor. Romantically, it’s parents doing whatever they can to support their child. The facts don’t change, but the meaning does.

And in the end, it’s that meaning - the romance we choose to layer onto the mundane - that makes a life feel worth living.

* Honorable mention here for F**k, That’s Delicious - another food-centric show that does an incredible job of highlighting the beauty found in food, often at hole-in-the-wall restaurants.

** There are objective issues with the Baseline Road area as shown in crime statistics, educational outcomes, etc. I’m not trying to minimize this at all. If anything, I hope this example underscores the notion that by taking the romantic perspective, we can find beauty and meaning even in tough situations.

You’re Not in the Culture, You are the Culture

What happens when we spend less time consuming and more time creating

INTRODUCTION

“Bill Gates said: wait till you see what your computer can become. But it's You, who should be doing the becoming, not the damn fool computer. What you can become is the miracle you were born to be through the work that you do.” – Kurt Vonnegut

Consumption is easier and more passive than ever. In the past, choosing a book or a TV show required at least a moment of intention. Now, algorithms serve up personalized, infinite feeds to keep us scrolling, streaming, and clicking with minimal effort on our part.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with consumption - we all need rest, information, and inspiration. But when consumption becomes our default state, we risk spending large parts of our lives passively absorbing rather than actively growing. The danger is that we look back and realize we’ve consumed far more than we’ve created - we realize we haven’t truly grown or left our mark on the world and those around us.

This consumption / creation imbalance has consequences at two levels. At the individual level, research shows that a sense of progress, however small, is one of the strongest drivers of human satisfaction. Creation can provide that progress. As we expand to the cultural level, the same dynamic holds true: communities thrive when enough people are willing to make, share, and build, not just consume and watch from the sidelines.

Technology will continue to make consumption easier, which means the responsibility falls on us to rebalance our time. We need to be more intentional about how much we consume, how much we create, and how the two interact to shape both our own lives and the cultures we’re part of.

David Foster Wallace saw this challenge years ago. He warned that it would continue getting “better and better and more and more pleasurable, to be alone with images on a screen… given to us by people who do not love us but want our money.” A little of that is fine. But if it becomes our default, his (quite dramatic) take was that, “in a meaningful way, you’re going to die. And the culture’s gonna grind to a halt.”

That’s the heart of this essay: building a way to notice when we’re tipping too far toward consumption, and deliberately shifting back toward creation. At the personal level, that means intentionally checking in on how we spend our time and energy. At the cultural level, it means recognizing our role not just as consumers of culture, but as participants and shapers of it.

Let’s start with the personal side of the equation.

the Consumption / Creation Framework

When you boil it down, most of our time falls into one of two states: consumption or creation.

Consumption: reading, watching, listening, scrolling. It’s input-oriented, and often passive

Creation: cooking a meal, journaling, painting, writing, hosting a dinner. It’s output-oriented, and almost always active

Neither state is inherently good or bad. The danger is in imbalance. Most of us spend the majority of our waking hours at work, and for many of us, this may be the only environment where we’re consistently producing tangible outputs. By the time we’ve exercised, made dinner, taken care of our children (4 legged or 2 legged), and handled the daily chores, it’s tempting to collapse into the couch and spend the rest of our time consuming. That’s understandable - but if consumption becomes the default, and we’re only creating in a work context, we lose the deeper sense of progress that creation can bring.

Research shows that progress is one of the biggest drivers of human well-being. The trick is that “progress” doesn’t just mean promotions or pay raises - it can be even more powerful in personal contexts. It can be as small as writing a page, sketching an idea, or teaching yourself a song on guitar. But you only get that sense of growth when you’re creating, not just consuming.

It’s important to stress: creation doesn’t always have to be tangible. Sometimes what you’re creating is a bond - a closer relationship with a friend, a deeper connection with your kids, or a sense of belonging in your neighborhood. These are valid, powerful forms of creation too, and they matter just as much as any outputs you may be able to hold or point at.

Personally, I’ve found it useful to set at least one creation-centric goal outside of work. Even a modest one (for example - starting a blog). Having something you’re building or working toward gives you:

A reason to claw back time and set better boundaries around work

A place to feel progress and momentum that isn’t tied to your job

A filter for what kinds of consumption are worthwhile (does this inform, inspire, or recharge me in service of my goal?)

There’s a broader discussion to be had here around the importance and benefits of goal setting in general, but the main thing for now is this: setting a creation-centric goal is the first step toward shifting your default state away from passive consumption, and toward active creation.

Auditing Our Consumption

Even if you set a creation-centric goal, the obvious question is: where’s the time going to come from? We’re all busy, and most days feel like there’s barely enough time as-is.

The place to start is by taking a closer look at how you’re consuming today. Not all consumption is the same. In my experience, most of it falls into three buckets: relaxation, information, and inspiration.

Relaxation: Sometimes you’re just tired and need to turn your brain off. That’s fine - it’s personal, and it’s necessary. The goal isn’t to eliminate downtime, just to make sure it’s intentional rather than default.

Information: We all consume information that helps us navigate daily life - from the weather forecast to local news to industry updates. This is useful as long as it actually informs your actions. Beyond that, it starts to become extra noise instead of useful signal.

Inspiration: This often overlaps with relaxation, but the key difference is intent. Inspiration consumption points forward - the cooking show you watch because you want to try a new recipe, the stand-up special that nudges you to try an open mic, the book that pushes you to start writing. This consumption can be enjoyable, but the ultimate intent is that at some point it will help inform or influence your own actions and outputs.

That last sentence is crucial. If we put relaxation aside, consumption is only good to the extent it actually informs or influences our outputs and actions. Otherwise, it’s just the empty calories of attention - satisfying in the moment, but ultimately leaves us feeling a bit worse off.

And this is where we often trip up. If you’re opening an app without knowing why, you’re probably not about to be informed or inspired - you’re likely just going to piss yourself off for no reason, and ultimately you’re about to waste time you could have spent more beneficially. The goal isn’t to outlaw consumption, it’s to cut back on the mindless kind so you can repurpose that time and energy toward something more likely to make you feel good about yourself.

In my own life, this meant admitting Duolingo was more entertainment than real learning, tightening my news habits into a simple (email-only, social media-free) morning routine, and letting my interest in stand-up comedy guide what I consume for inspiration. The details and specifics of my personal routine don’t really matter as much - the point is that once you know what you want to create, it becomes much easier to filter what’s worth consuming, and what isn’t.

Broader Cultural Implications

So far we’ve been looking at this balance between consumption and creation at the personal level. But the same imbalance shows up in our shared culture too. Many people want to consume or reap the benefits of a “cool culture,” but far fewer are willing to put in the effort to help build it.

City-level culture is a great example. Outside of a handful of U.S. cities - New York, LA, Miami, maybe a few others - odds are you can find someone complaining that “this place doesn’t have any culture.”

I’m reminded of a common sentiment I come across - this one about Charlotte specifically, but I’m sure there are versions of it in most other cities: “Everything here is great except there’s a lack of culture. It’s kind of just a transient place for young, white collar professionals to live for a little and make some money.”

To be fair, the sentiment is pretty on point. But the irony is often glaring: many of the people saying this are the exact white-collar transplants who moved here for jobs that are allegedly sanitizing the city. And this is the crux of it - when you complain about your city’s culture, to an extent you’re critiquing yourself. There’s a saying I heard not too long ago: “you’re not in traffic, you are traffic.” The same exact thing applies here: you’re not in the culture, you are the culture. You don’t just live in the city - you are part of what makes it what it is.

So if you think your city lacks culture (and maybe it does), that’s not just a critique - it’s an opportunity. When you say a city has no culture, what do you actually mean? No good restaurants? No music venues? No historic buildings or landmarks? You may not be able to open a restaurant or redevelop a historic building, but you could start a dinner club in your neighborhood, ask a local coffee shop to host an open mic, or rally support for preserving the historic spaces your city already has. We expect culture to be served on a platter, like the algorithm serves us on our phones. But by definition, culture is everywhere - you just have to put in a little effort to find the one that piques your interest.

It’s not just about restaurants or music scenes, either. A lot of the broader complaints about people feeling less empathetic, less engaged, and less connected to their neighbors are likely tied to the creation / consumption imbalance we experience at the personal level. The more time we spend passively consuming (i.e., doomscrolling on our phones), the less time and energy we have to actively connect in each other’s real (non-digital) lives.

It’s worth saying directly: culture isn’t only built in restaurants, venues, and landmarks - it’s also built in living rooms, classrooms, and parks. Social bonds are culture. Teaching kids, hosting neighbors, showing up for friends - these acts of connection are acts of creation too. They build the trust and texture that make a community worth living in.

The takeaway is simple in theory, but tougher to act on: unique, vibrant cultures require active participation from a diverse set of people contributing their own energy and ideas. If you’re not willing to actively seek out different cultural experiences, much less engage and contribute, I propose you lose the right to complain that your city (or your scene, or your team) “has no culture.”

CONCLUSION

The balance between consumption and creation isn’t just a matter of personal productivity - it’s a matter of how we experience life, and how we shape the places we live. Individually, creation fuels progress and satisfaction. Collectively, it fuels the culture that makes cities and communities worth belonging to.

The trap is that consumption feels effortless, while creation takes energy. That’s why it’s so easy to default into scrolling instead of practicing something new, spectating instead of participating. But the same thing that makes creation harder is what makes it meaningful: it demands effort, and leaves something behind.

David Foster Wallace warned that if passive entertainment becomes our staple diet, both individuals and culture will “grind to a halt.” The inverse is just as true: if more of us choose to create - even in small, humble ways - we expand our own sense of progress and keep our communities vibrant.

So the onus is on us: what’s one small thing we could create this week? Not someday, not in theory - but right now. A page, a meal, a gathering… anything really. However small, it counts. Because you’re not just in the culture - you are the culture.

Keep Your Identity Diversified

A response to Paul Graham on building a healthier sense of self.

INTRODUCTION

Paul Graham’s essay “Keep Your Identity Small” argues that the more labels we attach to ourselves, the harder it becomes to think clearly. He writes:

“If people can't think clearly about anything that has become part of their identity, then all other things being equal, the best plan is to let as few things into your identity as possible.

Most people reading this will already be fairly tolerant. But there is a step beyond thinking of yourself as x but tolerating y: not even to consider yourself an x. The more labels you have for yourself, the dumber they make you.”

It’s a compelling idea, and I agree with Graham’s underlying concern: identity can cloud judgment. When we anchor ourselves too strongly to an idea, it can become difficult to change our minds - even in the face of new evidence.

But I land somewhere else. Rather than shrinking our identities, I believe we should be more intentional about shaping them. That means grounding ourselves in foundational values and intentionally diversifying the roles we inhabit.

My goals here are:

To outline where I think Graham’s argument misses the mark

To offer a different approach to identity: one based on self-awareness, value alignment, and diversification

Where Graham’s Argument Falls Short

Is it a bit presumptuous of me to think I can refine the thinking of the man who founded Y Combinator? The answer is yes, but we’re already here so I might as well take a stab at it:

1) Minimizing Identity Isn’t Sustainable

Graham’s call to limit the composition of our identity may work in theory, especially for topics like politics or religion. But in practice, it’s unrealistic. We are social beings. We inevitably wear labels - as children, siblings, professionals, or community members. Identity is not optional. The real question is whether we’re shaping it or letting it shape us.

By suggesting we avoid labels altogether, Graham’s approach risks encouraging disengagement rather than introspection. Instead of keeping identity small, we should focus on keeping it examined.

2) Identity Doesn’t Have To Be Superficial

Graham focuses specifically on external or divisive identities - religion, politics, and profession. But identity can (and should) be rooted in something deeper. Rather than tying our sense of self to superficial titles, we can ground it in foundational traits: things like empathy, humility, and integrity.

These are traits that are valued and respected across eras and cultures. Because they are intrinsic rather than situational, they tend to be more stable and adaptable across the many contexts we move through in life.

A Healthier WAy To Build Identity

If identity is unavoidable, how do we engage with it productively? After thinking about it for way too long, I’ve found the following approach provides a solid start:

1) Take Inventory of Your Current Identity

Before shaping your identity, understand where it stands today. You can start by asking more surface-level questions:

How do I spend my time outside of work?

What activities dominate my week?

What qualities or perceptions would I be uncomfortable losing?

However, as you begin to peel the layers back, you’ll likely find yourself considering deeper, foundational questions:

Why do I spend my time where I do?

What values do I consider non-negotiable?

How do I want to be remembered by those closest to me?

Moving from surface-level to deeper lines of questioning helps reveal not just what you do, but who you’re becoming - and why. Exploring these layers often uncovers where we’ve invested meaning, sometimes unconsciously.

For example, someone might realize their self-worth is closely tied to being seen as productive, physically fit, or intellectually impressive. These identities aren’t inherently bad, but left unexamined, they can become blind spots - quietly influencing our choices, emotions, and priorities without us even realizing it.

2) Anchor Yourself In Core TRaits, Not Titles

There are two layers to identity:

Core identity: Who you are - your character, values, intentions

Contextual identity: Roles you play - employee, friend, parent, fan*

Your core identity should be grounded in values that transcend context. Traits like honesty or kindness aren’t bound to a specific job or relationship - they go wherever you do. When we lead with those, we benefit from stability even as the world around us changes.

3) When It Comes To Titles - Embrace Multiple, Meaningful Roles

While we can’t avoid contextual labels, we can diversify them. Instead of being defined by one role - “the athlete,” “the analyst,” “the parent” - we can deliberately expand our identity across a range of meaningful roles.

This has two major benefits:

Resilience: When one facet of our identity falters, others can support us.

For example, if your sense of self is entirely wrapped up in a prestigious job, and you lose that job, your entire world is likely going to get rocked.

However, on the contrary, if you have other parts of your identity that you can be proud of (e.g., being a father, being the best player on your beer league softball team, etc.), leaning into those other parts of your identity can help stabilize you as you get back on your feet professionally.

Growth: Adding new dimensions to our identities pushes us into new, uncomfortable environments that ultimately lead to personal growth.

There’s an art to not spreading yourself too thin, but it’s generally helpful to have one area of your life where you can really feel yourself stretching and actively growing. This is a feel thing and will vary for everyone, but as a rule of thumb, this should feel at least a little bit uncomfortable. Maybe it’s a bit trite, but growth comes at the edge of our comfort zone after all.

More tactically, this could be joining a writing group, volunteering, or learning a new skill - whatever floats your boat and gives you a healthy challenge.

I came across a quote recently that resonated here: “To be the noun, you have to do the verb.”

You want to be a writer? Put pen to paper. You want to be in shape? Show up at the gym. You want to be a mentor? Reach out to someone who needs support. Crafting your identity requires action.

CONCLUSION

Rather than minimizing your identity, take ownership of it. Build it on a foundation of values. Stay open to new roles. And check in with yourself regularly.

The goal isn’t to avoid being someone. It’s to become someone on purpose.

So ask yourself: What traits or titles define me today - and are they the ones I want shaping my future?

Thank you to Brandon Sloan and Tony S., Esq. for reading various versions of this essay.

*Note: As an OKC Thunder fan, I’ve been leaning into this portion of my identity heavily lately - I am a champion and no one can tell me otherwise

On Satisfaction

A quiet argument for being happily unremarkable.

INTRODUCTION

“To live a more meaningful life, we don’t need another vacation, a new hobby, or another workout routine. We don’t need an endless stream of self-improvement projects piled onto an already overstressed life. What we truly need is a life we’re not trying to escape, a life where play and joy are woven into our everyday work, allowing us to experience deeper fulfillment and uncover the breakthroughs we’ve been searching for.” - Chase Jarvis

There are 8 billion people on the planet today. Each of us is unique and complex, with our own desires and goals. But underneath all this complexity, we ultimately want the same thing out of life - to feel satisfied.

That may sound deceptively simple - and maybe it is. How we define satisfaction and how we pursue it varies widely depending on our upbringing and environment. Yet across all those differences, one truth remains: we want to feel good about our lives and how we’ve spent our time.

Still, many of us find ourselves stuck on some version of the hedonic treadmill - chasing the next accomplishment, believing satisfaction lies just beyond it. But it remains a moving target we rarely seem to reach.

If what we want is so simple, why do so few of us seem to find it for ourselves?

In my experience, several factors prevent people from finding satisfaction:

We overrate the abstract concept of “success”

We fail to define it properly

We compare ourselves to people who define “success” differently than we do

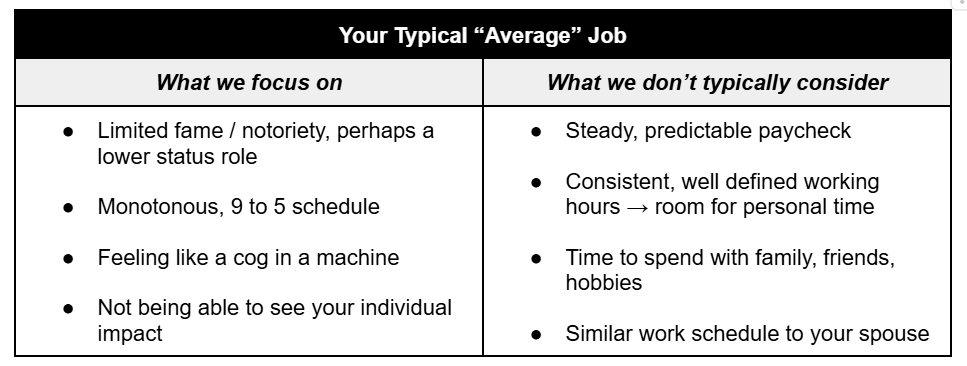

We underrate the “average” life

We overlook the positives of “average”, lower-status roles

We undervalue the benefits of routine

We’ll explore each of these ideas in more detail, but the bottom line is this:

The quickest way to satisfaction isn’t via achievement or status. It’s by finding contentment and gratitude in where we are today. To shoot you as straight as possible - satisfaction is found by embracing the “average” life.

To put it in more practical terms - we don’t find satisfaction by becoming a millionaire professional athlete, pop star, or titan of industry. There are countless examples of people who reach extraordinary heights of success, yet still wrestle with a sense of dissatisfaction. This is great news too, because let’s be real: most of us aren’t going to become any of those things. But even in our own fields, the reality is that most of us will fall much closer to the “average” section of the bell curve.

Maybe that comes off as a bit defeatist or depressing, but I hope I can convince you to find this somewhat liberating. If satisfaction is found independently of any external achievement, it means we already have everything we need to find satisfaction in our own lives - right now. All that’s left to do is start winning the battle between our own ears and finding security in who we are today.

I think many of us chase certain growth goals or accomplishments in an attempt to keep up with the Joneses. Finding gratitude in where we are today allows us to chase growth goals from a place of genuine desire and excitement, as opposed to playing an anxiety-riddled game of catch-up.

In other words: if we can be happy today - at “average” - anything else that comes our way is gravy.

“SUCCESS” IS OVERRATED

As mentioned above, we tend to overrate the abstract idea of “success” for two primary reasons. First, we often fail to define success clearly - if we define it at all. Second, we compare ourselves to others who pursue different versions of success, often at costs we wouldn’t choose for ourselves. Let’s explore both dynamics more deeply.

1) We fail to define “success” properly

One fundamental mistake many of us make is confounding success with status. Though related, they’re not the same. Success is internal - we define it and determine when we meet it. Status is external - it’s comparative, depending on how others perceive us. Waking up to this distinction unlocks two critical insights.

First, defining success is a choice - one that most people leave unmade. When we fail to consciously define success for ourselves, we generally absorb society’s default version: a prestigious job title, a certain income level, a trophy, or a line on our resume. These goals aren’t inherently wrong, but chasing them without true personal alignment often leads to exhaustion, burnout, and a persistent sense of dissatisfaction. You can pursue traditional goals if they genuinely resonate with you - but the key is to choose them, not inherit them.

(If you’re interested in a deeper exploration of this idea, I recommend thinking about your goals in the context of "resume virtues vs. eulogy virtues" - this is a framework that’s helped me personally think more clearly about where I derive satisfaction, and the kind of life worth aiming for. In short, resume virtues are skills you bring to the market, while eulogy virtues are the ones people remember you for when you’re gone.)

Second, and maybe most liberating: you can be successful without having high status. The more your definition of success diverges from traditional measures of status, the more uncomfortable this might be. It may mean taking a less glamorous job, earning less money, or stepping outside the script your peers expect you to follow. But clarity brings courage. When you truly own your personal definition of success, you’re free to pursue a satisfying life without seeking or depending on external validation.

The call to action here is simple enough: define success for yourself, and think about how closely it relates to status. Even if you don’t fully achieve your vision, the mere act of honest self-examination often shifts your mindset closer towards a sense of satisfaction.

2) We compare ourselves to people who define “success” differently than we do

Defining success on your own terms is crucial - it transforms your relationship with satisfaction in two important ways.

First, it helps you choose your cohort. In other words, once you define success for yourself, you can more deliberately identify the types of people worth admiring or emulating. Comparison is a natural human tendency we’ll always contend with, but if we must compare, we should at least be intentional about who we’re looking to for inspiration.

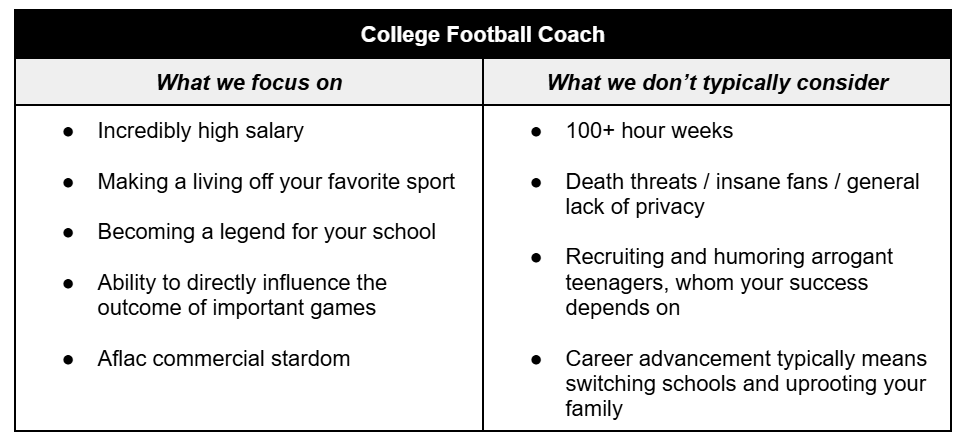

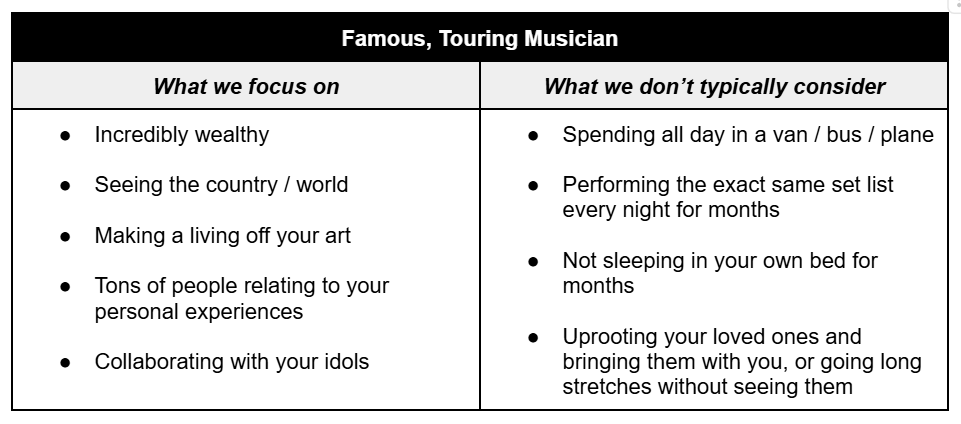

When we aren’t deliberate, we often default to admiring people in high-status roles - without fully considering the sacrifices those roles require. Worse, we tend to focus only on the glamorous aspects of their lives while overlooking the trade-offs. Two examples illustrate this pattern:

These examples lead to a second, deeper implication:

Your definition of success must also define the sacrifices you're willing to make.

If you’re absent-mindedly admiring someone with extreme status, but aren't prepared to endure the hardships that come with it, you’re setting yourself up for dissatisfaction. Extreme success often demands extreme trade-offs. Said differently: if you’re unwilling to endure the “cost” column of someone’s life, it doesn’t make sense to envy their “reward” column.

I can already hear someone thinking, “But Keith, if I were compensated like them, of course I’d be willing to absorb those trade-offs.”

But here’s the rub: you have to endure the sacrifices before you enjoy the rewards. In almost every high-status role, the heavy cost is paid upfront - long before the glamor and recognition arrive.

You always have a choice:

You can aim for a definition of success closer to traditional prestige - but know it will likely require extreme sacrifices.

Or you can pursue a more personal, non-traditional definition of success, accepting a different (and often gentler) set of trade-offs, like sacrificing external validation.

Both paths involve sacrifice - the difference lies in which costs you’re willing and able to absorb.